Bitcoin Cash Node Technical Bulletin

Evaluate Viability of Transaction Format or ID Change

Contents

- Summary

- Current Situation

- Costs and Risks of Change

- Reasons for Change

- An Alternative to Breaking Change

- Conditions for Change

- Conclusion

Summary

Changing transaction format or ID would create a precedent which would affect all non-node software that processes raw transactions. Because it is unknowable what software relies on the assumption of a fixed transaction format and ID, breaking that assumption would have costs and risks that are difficult to assess and contain where only the lower bound could be established by gathering evidence.

Transaction format can be upgraded in a way which would have predictable costs and risks. Most of the known desired features from transaction format changes can be introduced in a way with better contained costs and risks.

Because there exists a knowable node-contained-cost alternative, there is a natural deterrent to changing the format: it would be a greater burden on the one who pushes for a change than it would be to adapt his change to the alternative approach.

Current Situation

Transaction FORMAT

Here we define FORMAT as specifying only the data sizes and data types, not the semantics of individual fields.

- version, 4-byte uint

- input count, compact variable length integer

- transaction inputs

- input0

- previous output transaction hash, 32 raw bytes

- previous output index, 4-byte uint

- unlocking script length, compact variable length integer

- unlocking script, variable number of raw bytes

- sequence number, 4-byte uint

- ...

- inputN

- input0

- output count, compact variable length integer

- transaction outputs

- output0

- satoshi amount, 8-byte uint

- locking script length, compact variable length integer

- locking script, variable number of raw bytes

- ...

- outputN

- output0

- lock-time, 4-byte uint

There was never a precedent for changing the above TX format. There have been precedents only for changing semantics of some individual fields:

- version: BIP-0068

- unlocking script: Script VM upgrades

- sequence number: BIP-0068, BIP-0113

- locking script: Script VM upgrades

- lock time: BIP-0113

The version field was never locked down using consensus, so an assumption that a transaction's FORMAT could be inferred only from its contents would not hold, not without a block height context.

This could be changed by locking it down now, and then the assumption would hold only for never-before-seen version values.

Transaction TYPE

There are two main types:

- Coinbase;

- Regular.

The transaction version field is NOT used to indicate the main type. Instead, consensus verification uses simple heuristic to

infer the TX type: the first TX in a block is the coinbase TX, all others are regular.

Semantics of the previous output transaction hash and previous output index fields are inferred from the main type. For coinbase transactions it is locked

down to constants: a 32-byte 0 for the hash, and 4-byte 0xFFFFFFFF for the index. For regular transactions it is a reference to some previous transaction's output.

With BIP-0068, the regular type got divided into two sub-types:

- Interpret the inputs

sequence numberas sequence number; - Interpret the inputs

sequence numberas relative lock-times according to BIP-0068 semantics.

These two sub-types are commonly referred to as "v1" and "v2" transactions, and transaction version field is currently used by consensus only to distinguish the two sub-types. Any regular transaction

with version >= 2 is considered a v2 transaction, and others are considered v1.

There are no other consensus rules enforced over the version field, so on the blockchain there exist transaction with arbitrary data stored in the field. Without the context of the block height,

some past transactions could be considered to be v2 even though v2 was not defined when they were mined.

Also note that the standardness network rule requires version >= 1 && version <= 2.

Transaction ID

It is used to build transactions cryptographic commitment scheme and defined as the double SHA-256 digest of the whole transaction. It is a calculated field used for transactions Merkle tree, where transactions are leaf data and their TXIDs are leaf node hashes. Only the Merkle tree root node hash is written inside the block "raw" format, as commitment to all transactions in the block. The root node ID will also be a leaf ID (TXID) only if the block contains exactly one transaction, and that one transaction will then be a coinbase transaction. TXIDs of regular transactions will only appear in "raw" blocks when spent from, when referenced by an input of a newer transaction.

Even though most TXIDs of new transactions never get recorded into "raw" blocks, software processing transactions will still have to record TXIDs in local databases and caches.

To summarize, there are three things that define the transaction ID:

- The hashing algorithm: double SHA-256;

- The size of the digest: 32 bytes;

- The commitment preimage: whole "raw" transaction.

There was never a precedent for changing any of the above.

Costs and Risks of Change

Changing the FORMAT in node software is something that could easily be done by competent programmers, this is not where the majority of cost would be. There may exist software which relies on node API to hand it verified "raw" transactions. Changing the FORMAT would have the same effect as changing the node API, and the cost would then spread to node-dependent software. We can draw a parallel between node software and the Linux kernel. The Bitcoin Cash "kernel" is what runs the peer-to-peer electronic cash system, as opposed to a single computer's operating system. Even small changes there could have a cascade effect on the whole system, and everyone who depends on the system to conduct their business.

"We do not break userspace!" - Linus Torvalds

At least not without a very good reason. Change in transaction FORMAT or ID would affect all software that has to parse raw transactions, and the total cost would be the summed cost of upgrading all that software. The problem is not node software, or well known and open-source node-dependent software. We can evaluate that part of the cost, because it is known or, at least, knowable.

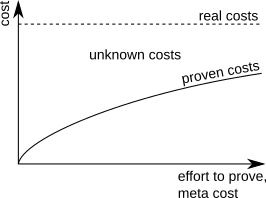

For the remainder we would have to expend large amounts of resources to communicate with and help migrate every known operator. Also, we would have to explore to get the lesser known ones, and it would be difficult to tell if we left any critical ones out. The cost of evaluation is itself a part of the total cost. We can visually illustrate this problem:

We can still expect to find, post upgrade, that someone had missed the memo. That is a difficult to assess risk for the Bitcoin Cash image and all Bitcoin Cash users who could be affected by a temporary disruption of services they rely on. With the breaking kind of change, a misstep in migration or risk assessment has the potential to result in catastrophic damage to the ecosystem that would be difficult to recover from.

To get the idea, here we list broad categories of systems that could be affected by a breaking change:

- block explorers,

- blockchain API providers,

- blockchain indexers,

- exchanges,

- payment processors,

- wallet backends,

- script debuggers,

- smart contract compilers,

- software libraries,

- etc.

This document merely highlights the nature of the costs and risks involved, and it could be used as a starting point of a process to solicit further input from potentially affected parties.

Reasons for Change

We can define two broad categories of rationales:

- Maintenance

- New features

Optimization is part of maintenance, and there were proposals to optimize the format. It was never really necessary because benefits would be some savings in node operating costs, where costs and risks would clearly outweigh the benefits.

Some catastrophic security flaw would be another, extreme, example of maintenance. In this scenario, fixing the flaw would be a matter of survival for the network, and if breaking the format or commitment scheme was the only way, then it would have to be done. Both transaction format and commitment scheme have been tested for almost 12 years, and we see it as unlikely that a severe security flaw would be discovered now.

There were considerations to increase precision of base units (fractional satoshis), which is presently not necessary. Only in the future, if the value of Bitcoin Cash would grow so much that it would be impractical to make small transactions, could it become a matter of great importance.

The cost of change at a later date would be greater because more software would be reliant on the fixed format and therefore affected. Would that be a good reason to upgrade the format now while the cost is smaller? That would be the case only if changing the format would be the only possible way to increase precision.

Similarly, there were considerations to permanently fix transaction malleability. This could be done by moving signatures from unlocking script into a dedicated transaction field. They would then be referenced from the unlocking script by signature opcodes, so signatures could sign inputs unlocking scripts, too. As we will see below, a new field can be added without changing the transaction format.

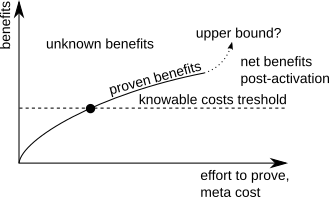

With new features, we must evaluate the costs vs benefits. The benefits will be contained to some subset of users who would use the feature. Maybe the feature would attract more users, in which case everyone would reap the benefits through increased value of Bitcoin Cash. Some kinds of features can have vaguely defined benefits because their value can come from enabled innovations beyond our control or knowledge, benefits could be speculative. Burden of proof for benefits is in proving at least some threshold level that would outweigh the costs.

How to set the threshold level when the costs are unknowable? It is impossible. We should instead strive to make the costs side of the scale knowable. If there is an alternative approach that has knowable costs and risks, then it is more likely that the alternative would stand a better chance of being implemented.

Lowering The Cost of Future Change by Versioning Transaction FORMAT

There would be value in paying off the technical debt by versioning transaction FORMAT, so any future upgrades that would prefer to change it would not have to take the whole burden of changing the format.

Old software does not expect the version field to have anything to do with the format of the TX it is being fed. First step would be locking the version field

using consensus, so it could later be used to signal any future consensus rules that would come after the version lock. Just the version lock would not break old software so only new, version-aware, software would benefit from

that.

It would still help with general preparedness for a future, breaking, change. From then onward, we could use part of the version field as an upgrade counter and match it 1-to-1 with applicable

consensus specification. As a consequence:

- Any

versionvalue seen before the version lock would relate many-to-many with "prehistorical" consensus specifications, therefore be indeterminate. However, it would narrow it down to pre-lock era. - Post-lock, the counter part of the

versionfield would be 1-to-1 with newer consensus specifications. We would have other bits free to allow us to have multiple kinds of TXes exist part of the same consensus specification, which would make the wholeversionfield relate many-to-1 with consensus specifications.

Alongside the counter, we could use a flag to signal whether an upgrade is breaking or non-breaking, e.g. when we increment the counter for a new HF, if it is non-breaking then we do not toggle the flag, and if it is, then we toggle

the flag. Old version-aware software would know the old state of the flag so could know whether it can safely process counter+1 TXes even if it knows it can not fully understand them.

In that scenario, upgraded software could know what rules apply to the TX even without knowing the block height, but it still needs to be upgraded so that it could match the version with applicable

consensus rules.

As the consensus upgrade counter part of the version field would be the most important and long-lived feature, the 4-byte* uint should be split into 16 bits

for the counter, 1 bit for the breaking flag, and 8 bits for the type of transaction. The remainder* would be reserved for future use.

(*) Because the version field was never locked, and if we want to enable context-free transaction parsing, we would have to use only the not-seen-prior-to-lock numbers to encode the newVersion so

the new version would have a range smaller than 4 bytes.

An Alternative to Breaking Change

Adding new fields to transactions is possible without breaking the format. There are two variable size fields where semantics have already been changed by upgrades, and are expected to be changed again in the future:

- unlocking script

- locking script

If the new fields are to be semantically attached to inputs or outputs, they can be inserted inside the related field as:

- unlocking script:

[PFX_FIELDNAME, or] - locking script:

[PFX_FIELDNAME.]

The PFX_FIELDNAME would be a constant "magic" byte, PreFiX to the real locking script, and fieldValue the

new field to be added. This approach was first proposed by Calin Culianu as part of discussion of a specific upgrade. Consensus

code would read the PFX byte and trigger required consensus code which would read the field and enforce required semantics over the field(s), and then pass the realLockingScript or realUnlockingScript to

the Script VM.

The PFX_FIELDNAME could be decided to match a disabled Script opcode, in which case it would be a hard fork change:

- Unupgraded node software would fork the blockchain because, from the point of view of unupgraded software, such

locking scriptwill be seen as starting with a disabled opcode. - Unupgraded non-node software should already know how to deal with disabled opcodes found on the blockchain, so should not break when encountering them. From its point of view the

PFX_FIELDNAMEbyte could be some new data push opcode followed by random data.

It could be enveloped by a data push opcode followed by an OP_DROP, in which case it would be a soft-fork change:

- unlocking script:

[OP_DATA_X PFX_FIELDNAME, orOP_DROP] - locking script:

[OP_DATA_X PFX_FIELDNAME.OP_DROP]

Because the push opcode depends on the length of data to be pushed, it would not be enough to look for a "magic" byte, here it would be more complex to detect because it would be magic pattern: any data push opcode that is followed

by the magic PFX_FIELDNAME byte as first byte of the data, and followed by an OP_DROP after the data.

In this case all unupgraded software would interpret the prefix as a no-op and unupgraded nodes would continue to accept new transactions, even when unaware of any consensus rules applied to the no-op pattern.

The two above methods would extend inputs or outputs with new field(s). What if the new field would be independent of inputs or outputs? For that we would have to sacrifice one input or output to be a data carrier for the whole array,

and use the version field to indicate that is the case. It would be exactly one input or output, and placed as the 1st output of a transaction.

In case of a field carrier input, it could be of the following format:

- previous output transaction hash: 0x00...01

- previous output index: 0xFFFFFFFF

- unlocking script length: to match

- unlocking script:

PFX_FIELDNAME<[element0][element1]...[elementN-1] - sequence number: 0x00000000

Consensus would have to ignore the fact that the referenced output does not exists, so this is viable only as a hard-fork. There is precedent for this in coinbase inputs. Unupgraded node-dependent software would see this as an ordinary input so some risk would remain in that dependent software may want to query the node for the non-existent parent output. The node could provide a dummy output to address that, but we will see below that a carrier output is a better option.

In case of a field carrier output, it could be of the following format and it would require a hard-fork:

- satoshi amount: 0x0000000000000000

- locking script length: to match

- locking script:

PFX_FIELDNAME<[element0][element1]...[elementN-1]>

Consensus would know that such output is unspendable and it would never have to be recorded in the UTXO database.

Soft-fork variant would be possible, too:

- satoshi amount: 0x0000000000000000

- locking script length: to match

- locking script:

OP_RETURN OP_DATA_X PFX_FIELDNAME<[element0][element1]...[elementN-1]>

With the soft-fork variant, PFX_FIELDNAME would have to be chosen not to conflict with known OP_RETURN protocols.

Outputs have less overhead, 10 bytes for the hard-fork variant, and should be the preferred method. Nodes would naturally be aware that the output is a "magical" output. They would parse the locking script and populate the TX database and cache. The output itself, however, would never make it into the UTXO database because it is unspendable.

Unupgraded non-node software would see it as a real output starting with a disabled opcode, so should not break when encountering them.

Conditions for Change

Because there exists an alternative where the cost would be contained to node software, a proposal to change it by breaking it would have to demonstrate that:

- Benefits of the breaking change are significantly greater than the benefits of a non-breaking alternative or at least, any difference in benefits must make up for the difference in costs.

- Majority of known stakeholders have been accounted for in cost estimation, as many as reasonably practicable.

- Majority of known stakeholders have accepted to bear the cost, even knowing there is an alternative which would not require them to bear it.

On the other hand, a non-breaking alternative would have to demonstrate that:

- Benefits are greater than the cost.

- Node developers and miners are OK with the change.

- Other stakeholders are not affected, unless they want to use the new feature.

We can observe here that the burden of proof is much greater for a breaking, non-backwards-compatible change. It would have to involve the broad ecosystem, everyone who could have their software broken by the change. The coordination and consensus building effort would be a big meta cost shared by all, and there is no guarantee that the meta cost would be recouped by successful activation.

This is not a matter of soft forking vs hard forking, which are concepts that pertain solely to the nature of node consensus with no consideration for other software and services. Hard fork protocol upgrades are the preferred way for Bitcoin Cash. Most hard forks are backwards compatible with regards to dependent software and costs have been contained to nodes and miners. We can observe here that not all hard forks are the same. With the non-breaking type everyone can simply upgrade the node, and all their other software will continue to function. With the breaking type, everyone would have to update not just the node, but all their dependent software.

Note that presently there is one Bitcoin CasH Improvement Proposal (CHIP) which proposes to roll out new features in a way that would break both the TX FORMAT and TX ID:

The CHIP owner has made a good start in attempting to evaluate costs and risks, but because of nature of these costs and risks it is hard to estimate how much more work would be required to capture enough of them, or to even decide how much would be enough to be as-much-as-reasonably-practicable.

Conclusion

We have shown that not all hard forking upgrades are the same. There are hard-er forks, in that they would break node-dependent software. We have shown that the burden of proof for such a change is much greater than for a non-breaking change.

While not impossible, a proposal that attempts to make a breaking change will have to strongly demonstrate its superiority over a non-breaking alternative in the context of stakeholders.

As time goes on, and the network grows, there will be more reliant software. Therefore, the cost of breaking will grow with time so the likelihood of making new precedents and breaking what has never been broken is expected to only decrease with time.

Links:

- Repository link of this announcement: GitLab